Opposition to the Cancer Virus findings by the medical profession

Rife had isolated the cancer virus, but a mountain faced him. The filtration versus non-filtration argument prevented those in the field of bacteriology from charging in the direction that Rife, Kendall and Rosenow had shown. Instead, the bacteriologists were squabbling, being skeptical and waiting to see which way the wind blew. The microscope experts also were standing on the sidelines. They had heard or read about the new Rife microscope, but only Rife and Kendall had one, and few knew a second microscope existed in Kendall’s Chicago laboratory. Rife wasn’t providing the professionals much information. He had his cancer virus to test and test and test. And he had a new, more powerful microscope that he wanted to build. Johnson and others were seeking meetings, writing letters and asking for demonstrations. Rife was polite and helpful at times, but often just never answered his mail. The scientific problem of curing cancer demanded his full attention.

Despite all the outside pressure in 1933, Rife did accomplish three major feats. He wrote a paper which provided a clear direction for future bacteriologists. He continued his cancer research on cultures and guinea pigs-hundreds of them. And he built his new, super microscope.

Dr Rife: Viruses and Rickettsia of Certain Diseases

Rife’s brief 1933 paper was titled, “Viruses and Rickettsia of Certain Diseases.” A few significant passages are quoted: “The existing theories regarding the viruses are entirely unsatisfactory and sadly wanting of further elucidation. Therefore, we shall expound our theories at the outset with the hope that other workers may find them sufficiently basic to serve as an incentive for checking our observations. observations made during three days, in Dr. Kendall’s laboratory at North University Medical School in Chicago. Assembled there to carry out the experiments were Dr. Kendall, Dr. Rosenow and myself. Owing to the novel and important character of the work, each of us verified at every step the results obtained. ‘The above mentioned reports serve to establish two important facts. Fist that it is possible to culture viruses artificially, – and second, that viruses are definitely visible under the Rife Universal Microscope.’

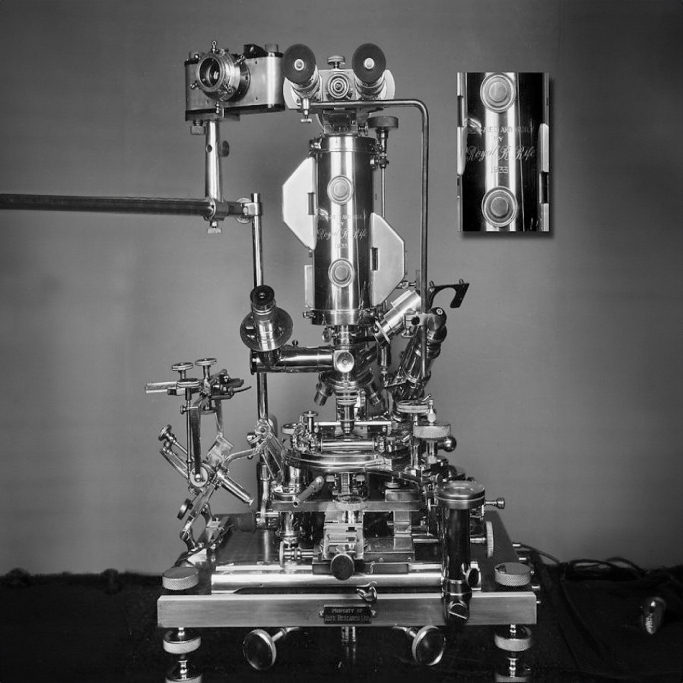

The microscope Rife built in 1933 was the largest and most powerful of the five he built. One was built in 1920, another in 1929, the “Universal” officially completed in 1933 although it may have been used in an uncompleted form in 1932 as the above report suggests, another microscope in 1934, and one in 1937 which was finally finished in 1952. Some parts from pre-existing ones were used for later ones. Wile the 1929 microscope was a “super” microscope compared to all other commercial microscopes, with a working magnification between 5,000x and 17,000x, the “Universal” Microscope of 1933 possessed a resolution of 31,000x and a magnification of 60,000x (as described in the terms of the time).

An example of the power and clarity of Rife’s microscopes compared to other light microscopes is provided by the Smithsonian report of 1944: “In a recent demonstration of another of the smaller Rife scopes (May 16, 1942) before a group of doctors . . . a Zeiss ruled grating was examined first under an ordinary commercial microscope equipped with a 1.8 high dry lens and x 10 ocular, and then under the Rife microscope. Whereas 50 lines were revealed with the commercial instrument and considerable aberration, both chromatic and spherical noted, only 5 lines were seen with the Rife scope, these 5 lines being so highly magnified that they occupied the entire field, without any aberration whatsoever being apparent.

Following the examination of the grating, an ordinary unstained blood film was observed under the same two microscopes. In this instance, 100 cells were seen to spread throughout the field of the commercial instrument while but 10 cells filled the field of the Rife scope.” While Rife was working, so was Dr. Milbank Johnson. Up to this point in time, he seemed to have a minor role-simply putting Rife and Kendall together, sponsoring a dinner, etc. But beginning in 1933, Johnson began to work and organize. He wrote letters. He informed important doctors of what was happening. And he started to plan for the treatment of people who had cancer. Rife was the pure scientist and undoubtedly a genius of the first order. Milbank Johnson was the political doctor in the best sense of the term. He was a man of the world and an unstoppable executive force.

When the scientific honors are finally bestowed on the men who found the cure for cancer and brought it to the world, Dr. Milbank Johnson will be in the first row. Johnson in the next few years would send Rife numerous letters-informing him, advising him, telling him he was coming to visit and bringing so and so, prodding and subtly pushing Rife. Even if Rife had wanted to avoid Johnson (which he did not), it probably would have been impossible. Johnson was an enormous force of nature-a social energy who, in his own way, was moving mountains. Johnson’s letters indicate that Alvin Foord, the pathologist who later claimed he had little contact with or knowledge of what happened in the 1930s, was in fact deeply and personally involved. In July 1933, Johnson met Dr. Karl Meyer, the Director of the Hooper Foundation for Medical Research of the University of California in San Francisco. Meyer would later serve on the Special Medical Research Committee of the University of Southern California which sponsored the cancer clinic in 1934 and the other clinics which followed.

Years later Meyer would try to claim he had only visited Rife once and looked into his microscopes, not being sure of what he saw. The record clearly indicates a very different situation. In February 1934, To Rife: ‘You made quite a tremendous impression on Dr. Meyer and I think the whole subject of filtrable bacteria and the microscope were advanced.” In March 1934, Meyer wrote to Rife, “I am still ‘dreaming’ about the many things you were kind enough to show me last Saturday. As soon as I can tear myself loose I will accept the privilege of coming back and bringing with me some of the agents which produce disease.” In the years to come, the Hooper Foundation would be given a Rife microscope of its own, cancer cultures would be obtained from San Francisco surgeons, and motile colored bodies, “presumably your BX,” would be reported to Johnson by Dr. E. L. Walker of the Hooper Foundation, working under Dr. Meyer.

Dr. Meyer was another non-hero when the AMA and government pressure was imposed. He later served on national medical committees with Dr. Rivers of the Rockefeller Institute and Morris Fishbein of the AMA. But by then he was very silent about the cancer research in which he participated in the 1930s. In 1933 and 1934, Meyer was one of the growing circle of influential doctors whom Johnson was cultivating as he prepared to organize his credentialed committee to oversee a cancer treatment and then bring it to the world. Johnson was also vigorously defending the filtration theory. When Dr. William J. Robbins of the University of Missouri reported in a Science News letter that “one as yet unsettled question about viruses is whether or not they actually are living organisms,” Johnson wrote to him and referred him to the articles by Kendall, Rife and Rosenow.

He also put himself on record: “I have seen with Dr. Karl Meyer of the University of California the filter passing forms of such diseases as hog cholera, psittacosis, and a very infectious disease of chickens affecting their throat. . . . It seems strange to me that others are having difficulty first-in producing the filter passing organisms; and second-that there should be the least doubt about their existence, form, characteristics, or size when they are so easy to obtain and so easy to determine. . . . I feel quite sure that Dr. Kendall in Chicago who has the Rife microscope nearest to you will verify what I have said and show you these for yourself .” But while Johnson was willing to serve as a frontline soldier in the filtration war, his true role was as a general in the cancer war. In the Spring of 1934, he rented the “ranch” of a member of the famous Scripps family of the Scripps Oceanographic Institute. The ranch in La Jolla outside San Diego was to be used as a clinic for the first treatment of cancer victims using the Royal Rife Machine. Johnson was moving, pushing and manipulating. He wrote to Kendall on April 2, 1934, “I hope you and Gertrude will be able to spend your vacation in La Jolla this year. . . . It is going to take all the ingenuity of a Rife and Kendall plus the little help that a poor M.D. like myself can give before we are going to be able to crack this nut. But we are going to crack it if we have to drop it from a height of ten miles.”

Johnson exposed his own driving motive: “You don’t know how hard it is for me to keep my shirt on in this whole proposition because I can’t help but see in my mind’s eye the tens of thousands of discouraged, hopeless, suffering individuals dying by inches with cancer who might be saved. Of course I know that you and Rife are interested in this thing from a pure science standpoint, but unfortunately, my training has been largely mixed with the humanities and it is real sickening to see the suffering and hopelessness of the victims of this terrible disease.” At the same time, Johnson began “prepping” Rife for the upcoming clinic.